The NRA is in free fall.

May 7, 2021 at 7:00 a.m. EDT

Our research tracked gun politics in the United States from 1945 to 2015. With that background, we do not expect Congress to pass new national legislation. Gun regulation advocates tend to mobilize after a high-profile shooting, after which the momentum dissipates. Their opponents in the gun rights movement, anchored by the National Rifle Association, remain strong and active without relying on media attention.

Still, some facts suggest next time might be different.

Gun rights groups have more money and staying power than gun regulation groups

Well-organized groups fight on both sides of the gun debate, but their power is unequal. Our analysis of tax data shows that, as a whole, gun safety groups bring in, on average, less than 10 percent of the funding raised by gun rights groups.

Founded shortly after the Civil War, the NRA has long dominated gun politics. Since the mid-1970s, the group has burrowed into conservative politics, garnered massive financial support from both members and the firearms industry and cultivated a small but passionate constituency. While other gun rights groups come and go, the NRA has consistently accounted for about 90 percent of the movement’s publicity and the lion’s share of the movement’s resources, our analysis of New York Times coverage and 990 tax return data finds.

Gun control groups, conversely, struggle to maintain consistent media attention, financial support and national influence. Groups with shared interests compete for resources. The most prominent gun safety group has accounted for about half of the movement’s visibility and funding, we find. The Brady Campaign to Prevent Gun Violence (formerly, Handgun Control Inc., and now just known as Brady), shared leadership with the National Coalition to Ban Handguns through the mid-1980s; with the Million Mom March and the Violence Policy Center for a few years after the 1999 Columbine High School shooting; with Mayors Against Illegal Guns (now Everytown for Gun Safety) since 2007, and with Moms Demand Action and Americans for Responsible Solutions (now Giffords) since the 2013 Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting. The emergence of March for Our Lives, founded by survivors of the 2018 Parkland High School shooting, is a recent example of how new groups become important to the gun safety movement every few years.

We find the gun control movement is less steady than its political opponent. When enthusiasm wanes, groups reconfigure, merge, or disappear, and political leadership, messaging and organizational changes occur every few years.

Most Americans support firearm restrictions, but few consider it an urgent priority

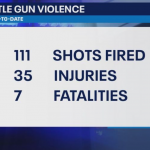

While a majority of Americans support stricter firearms restrictions, few put such regulations at the top of their political concerns — except after a visible and dramatic tragedy. Gun safety groups must therefore link their efforts to current events. Since the 1960s, their agendas have shifted from stopping street crime, assassinations, and handguns to controlling semiautomatic weapons, enacting background checks and ending mass shootings, even though mass shootings represent only a small portion of gun deaths each year.

The U.S. political agenda is crowded. To get attention, any advocate must link their issue to something at the top of the news. Moms Demand Action has added the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act to its action items. Brady is emphasizing how “gun violence is a racial justice issue,” and March for Our Lives has a new initiative with “BIPOC youth organizations and activists on the ground.” Such agenda expansion is common, both in this case and in organizing efforts more broadly.

The NRA’s stable base of support, by contrast, allows it to choose when to engage with the public debate. After visible mass shootings — like the recent FedEx attack in Indianapolis or the Atlanta shooting of six Asian women and two others — the group typically goes silent, save to offer the much-mocked “thoughts and prayers” and castigate opponents for politicizing the moment. The NRA counts on momentary passions cooling before legislation can pass. Moreover, the group is organized around a simple and clear agenda: resisting restrictions on access to firearms. Organizing around “no” is easier than advancing any kind of affirmative agenda.

U.S. political institutions favor the status quo

U.S. political institutions were designed to slow or stop ambitious policy changes, making defense structurally easier than offense. Even with a sympathetic president and House, the Senate remains an obstacle, filibuster or not. The NRA still represents a critical faction of the Republican base, capable of threatening an incumbent with a serious primary challenge. A Supreme Court packed with Second Amendment expansionists could be a final backstop against new gun regulations.